À côté du Salon des vins de Loire se tiennent à Angers et alentours d’autres rassemblements tels que La Dive Bouteille, la Levée de la Loire, le Salon des Pénitentes ou celui des Anonymes, tous tendance bio. Le plus important est Renaissance des Appellations, qui se déroule au Grenier St Jean à Angers rive droite, désormais trop petit tant l’affluence grandit chaque année. Son initiateur en est Nicolas Joly, propriétaire de la fameuse Coulée de Serrant en Savennières et grand prêtre de la biodynamie connu dans le monde entier.

Après les vins rouges de Loire, Eric Asimov, critique vin au New York Times, se penche sur le blancs — les Savennières et la Coulée de Serrant — et sur le gourou Joly lui-même (ci-dessous lévitant devant ses vignes).

THE THINKING PERSON’S WHITE WINE — If you are looking for a winter-weight white wine, one that’s substantial enough to warm the insides yet elegant enough to dance intimately with many different foods, I have got a name for you: Savennières. I love it, but I will concede it is not particularly likable. It is not an easygoing, friendly wine, it requires a commitment, which is not necessarily a step that everybody wants to take.

I understand the feeling. Just as I often prefer a thriller to a work of literature, I sometimes don’t want to make the effort to ponder a wine. I just want to enjoy it. At those moments, I would leave the cork in the Savennières. But given the proper time, energy and sense of resolve, the rewards of a good Savennières are many.

This complicated wine is from the Anjou, a region on the sinuous Loire River near the city of Angers. Savennières is a tiny appellation, with wines composed entirely of chenin blanc planted largely on south-facing slopes on the north side of the river. Most of the wines will be labeled Savennières, though a few bear the sub-appellations Roche-aux-Moines and Coulée de Serrant. Farther east near the city of Tours are Savennières’s primary chenin blanc siblings, Vouvray and Montlouis.

Like riesling, chenin blanc has the tremendously versatile capacity to produce wines ranging from bone dry to lusciously sweet. Up until the mid-20th century, Savennières was typically a sweet wine. Now, while you might occasionally find a sweet version, almost all the wines are entirely dry, unlike, say, Vouvray, which still produces a fair amount of delicious demi-sec and intensely sweet moelleux wines.

How does Savennières differ from a Vouvray? I have always found most dry Vouvrays to be slightly easier-going and more accessible, without the density, concentration or austerity of Savennières. Good dry Vouvray can age beautifully and evolve in complex and fascinating ways, but it doesn’t always require the same level of mental engagement as Savennières.

The challenges posed by Savennières begin almost immediately. Even a youngish wine, poured into a glass, can occasionally seem suspiciously dark, as if green-gold youth had aged prematurely into an oxidative amber. Right out of the bottle, Savennières often has a strange aroma, almost like wet wool, organic but not something we conventionally associate with wine. When I had less experience with Savennières, I often wondered on first sniff whether the bottle might be corked or flawed.

On the palate, Savennières is dense but not heavy, voluminous yet graceful with an exquisite succulence that draws me back again and again.

Almost invariably, the wine would turn out to be perfectly sound. With time and air, this aroma evolves into less-daunting components like straw and sweet grass, which combine with the more typical chenin blanc characteristics of flowers, chamomile and honey. This texture is one of the most alluring aspects of chenin blanc, and particularly of Savennières. It had better be attractive because when Savennières is young, the acidity can be unyielding and somewhat impenetrable. Even so, the wine feels wonderful in the mouth, and the flavors persist deliciously long after you swallow.

Eventually, with air, individual flavors begin to emerge and insinuate themselves, echoing the aromas with the underlying addition of a fine mineral tang, expansive and closegrained. With age (they can go for decades), the wine deepens yet never quite cozies up, remaining somewhat austere in contrast to, say, a plump white Burgundy. Savennières, especially young ones, most definitely benefit from decanting. They blossom when cool but not icy.

Because the appellation is so small, chances are you will come across maybe 10 or 12 producers if you are lucky enough to find a good selection. Many of them are long-established names. One of my favorites is Château Soucherie. I loved its 2010 Savennières Clos des Perrières, a mellow, complex wine with great finesse. Other established names well worth seeking out include Château d’Épiré. The 2012 vintage of its old-school Cuvée Spéciale, aged in chestnut barrels, is already available, and while it’s lovely now, it will only get better with time. Domaine aux Moines makes a more exuberant style of Savennières. Its 2010 Roche aux Moines is lean yet rich, pure and delicious.

Domaine du Closel makes a cuvée, La Jalousie, that offers an attractive introduction to Savennières for around $20 to $25 a bottle. Several newer names are injecting energy into the appellation. Damien Laureau’s 2007 Le Bel Ouvrage is a beautiful, intriguing wine, tightly knit and silken textured, understated yet with much to offer. Eric Morgat is another relatively new name worth following. His 2010 L’Enclos is clean, fresh, tight and full of mineral flavors.

Hovering over the appellation is the best known, most expensive and most baffling domaine, Nicolas Joly, among whose holdings is Savennières’s most hallowed terroir, the Clos de la Coulée de Serrant. Mr. Joly may be best known nowadays as the guru of biodynamic viticulture. Biodynamics has come to be widely accepted (though fervently dismissed as well), but Mr. Joly holds other beliefs that may be equally or even more controversial.

For example, while all wine producers wish to harvest ripe grapes, what constitutes ripe is subjective. Mr. Joly seeks grapes that have begun to shrivel and, he hopes, develop botrytis, the noble rot that is an essential component of wonderful sweet wines but not always desirable in dry wines. Fermented until dry, the Joly wines are typically high in alcohol, 15 percent or more as against the more typical 13 to 14.5 percent. Mr. Joly also recommends the extreme measure of decanting his wines two days in advance.

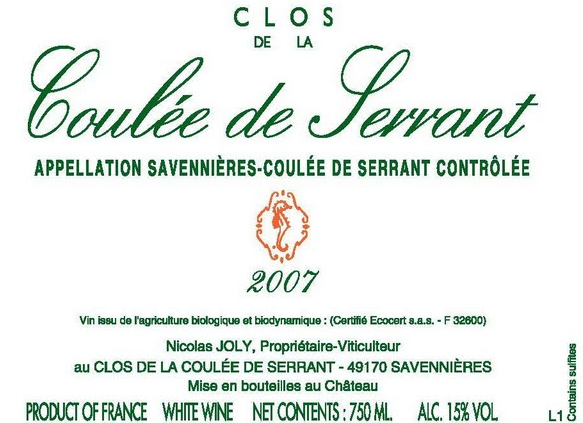

I have tried Mr. Joly’s methods, most recently with a 2007 Clos de la Coulée de Serrant, the crown jewel of Savennières.

The wine pours out almost an amber brown, as if it were oxidized. It’s not. In fact, it’s complex and gets better the longer it sits in the decanter. But it’s never altogether pleasant. The alcohol simply creates too much heat on the palate.

By contrast, Les Clos Sacrés 2007, the basic Joly Savennières, is far better balanced and enjoyable, rich yet austere, even though it is 15 percent as well. The Joly wines are the biggest puzzle, eccentric yet not lovably so. I prefer the pleasures of Savennières’s more conventionally intriguing wines.