From VINE PAIR | April 11, 2017

PÂQUES : considérations archéologiques américaines et israéliennes sur le vin au temps de Jésus-Christ.

It’s hard to ignore the prominence of wine in the Bible. According to Jancis Robinson’s Oxford Companion to Wine, the vine is mentioned more than any other plant. A study at Brigham Young University in Utah found that the word yayin, one of many Ancient Hebrew words used for wine, is used 140 times in the Old Testament.

Wine plays a central role in the biblical narratives.

The first thing Noah does post-flood upon reaching dry land is plant a vineyard, get trashed, and pass out in his tent. Later, Jesus shows up at a wedding in Cana with his disciples. During the reception, the wedding party runs out of wine and Jesus performs his first miracle, turning water into wine and saving the newlyweds from an epic faux pas. And toward the end of his life, Jesus uses wine at the Last Supper / La Cène as a symbol of his blood (see various illustrations below)

Le sacrement de la dernière cène, Salvador Dali, 1955, National Gallery of Art, Washington

Le sacrement de la dernière cène, Salvador Dali, 1955, National Gallery of Art, Washington

What kind of wine were they drinking?

Wine grapes have come a long way since the days of Jesus and King David. There have been millennia of mutations and cross pollinations, displacement from wars and different cultures adopting land throughout time, so it is very hard to pin down what grapes were grown and used for making wine in the Middle East. It’s not for lack of trying, though. Winemakers in Israel have been working to find the varieties used in antiquity through DNA testing and archeological digs. They have identified about 70 native varieties, The New York Times reports, with 20 suitable for winemaking. It is pretty exciting stuff. One winery — Recanati — produced a wine called “marawi” in 2015, the first indigenous grape made into wine in modern Israeli history.

But aside from this pretty exciting DNA project, it is tough to know what your favorite Bible character might have had in his wine glass. What is easier to wrap your head around is how wine was made back in the day. Archeologists have found ancient wine presses as well as Egyptian tomb paintings depicting the winemaking process. This, along with the writings of Pliny the Elder, gives us a sense of the style of wine of the time.

La Cène, Fritz von Uhde, 1866, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

La Cène, Fritz von Uhde, 1866, Staatsgalerie, Stuttgart

But which variety of grapes would have been used? Eliyashiv Drori, an œnologist at Ariel University in the West Bank, uses DNA testing to determine what types of wines would have been drunk by King David and Jesus. He told the New York Times in 2015 that one likely variety was the dabouki, a grape native to Armenia which produces a white wine that Drori described as “cashewlike” and “a little bit tropical.” On the other hand, the archaeologist Patrick McGovern, told the œnophilic website Vivino that the wine in question was “something like a modern-day Amarone,” a rich red variety from northern Italy.

How were they making wine?

The winemaking process began with structures built from stone in the vineyards. These were the wine presses and they contained one large, square platform that was a few feet deep. Into it, you would dump the grapes. Sometimes these wine presses had a trellis built over them with ropes hanging down to hold onto while stomping around. As they stomped the grapes, the new juice would flow into yeqebs (wine vats) and was then collected in earthen vats and stored in a cool place or under water to begin natural fermentation.

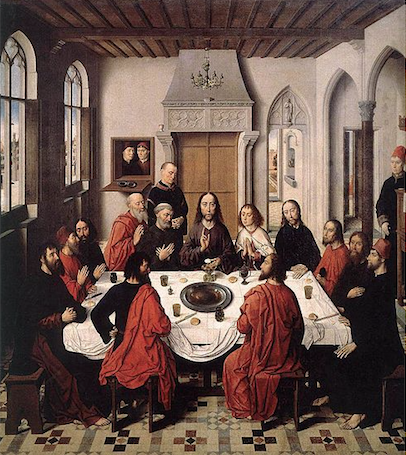

La Cène, Dieric Bouts, 1464-67, église Saint Pierre de Louvain

La Cène, Dieric Bouts, 1464-67, église Saint Pierre de Louvain

This is where it gets interesting. They would keep the trodden grapes skins and use them later. Wine to the ancients was in most cases more of a survival product then a luxury, although the wealthy were said to make good wine that could last a few years. To the commoner, wine needed to last through to the next harvest, and without the technology we have today, they had to make sure the new wine didn’t ferment for too long or it would turn to vinegar. For this reason, it was common practice to add the must, which contained some extra natural sugar, to the new wine so that it would overwhelm the yeast, stopping the fermentation before the wine entered the vinegar zone. The must was also mixed with water for fruit juice for women and children who were not allowed to drink wine.

What did wine taste like at that time?

Because of no filtration, biblical wine was probably not smooth but a bit harsh from constant exposure to the organic material that we usually filter out today. The added must would increase the alcohol level a bit and extract an extra layer of tannin, making it a bit rough around the edges. The residual sugar levels was higher, which would add juicy roundness to the harshness. Red wine was probably be very dark in color, which is why in the Bible, Jesus uses it as a symbol for his blood.

And there would be no such thing as white wine. The ancient people were not separating white wine skins from the juice and then fermenting separately. Wine made from white grapes would probably be amber in color from oxygen exposure and interaction from the must. It would also be harsh and juicy, with less tannin but enough to really go well with the local foods.

La Cène, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929), non daté, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

La Cène, Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret (1852-1929), non daté, Musée d’Orsay, Paris

Wines at the time of the Bible were big, round, juicy, austere red or amber in color. That austerity was often cut with water. It was basically required in the ancient world to dilute your wine with a little bit of water to round it out, and you were seen as a barbarian if you didn’t do so. Pliny dedicates some of his writing to different ratios of dilution, depending on the wine, so as not to comprise the bouquet of a wine.

If the couple getting hitched in Cana were wealthy, then Jesus and his Apostles were probably drinking new wine that was diluted just right so that it was round and fruit-driven, with just the right amount of sweetness for the wedding guests to proclaim that it was the best around.

À gauche, La Cène, partie de La Maestà, Duccio di Buoninsegna, 1308-11, musée dell’Opera Metropolitana del Duomo, Sienne

À droite, La dernière cène, vers 1175, mosaïque du transept de la cathédrale Santa-Maria-Nuova de Monreale (Sicile)

What is the closest wine we have today to the one they were sipping?

In Judea more specifically — near Jerusalem where the Last Supper is said to have taken place — archaeologists have found a jar inscribed with “wine made from black raisins”. This means that winemakers may have used grapes dried on the vine or in the sun on mats to create sweet, thick drinks. At sites nearby in the region, jars labelled “smoked wine” and “very dark wine” have also been found.

While it was common to water down wine, there was a taste in Jerusalem for rich, concentrated wine, according to Dr Patrick McGovern. Spices and fruits — including pomegranates, mandrakes, saffron and cinnamon — were used to flavour such wines, and tree resin were added to help preserve them.

The wine drank at the Last Supper might resemble the mulled wine some of us drink at Christmas. It is hard to come up with a modern-day wine that approximates what the Bible’s characters were drinking. Especially for the red as modern tech does away with the issues that they were facing. But tannat from Uruguay is probably the closest you would come.

For white, what is known as “orange” wine is most likely what they would have been sipping. Kabaj’s Rebula from Slovenia is a good example, or Bodegas R. Lopez de Heredia from La Rioja in Spain.

La Cène d’Ognissanti, Domenico Ghirlandaio, vers 1640, couvent d’Ognissanti, Florence

La Cène d’Ognissanti, Domenico Ghirlandaio, vers 1640, couvent d’Ognissanti, Florence